Back in 1960’s it had been found that by focusing a pulsed beam of a ruby laser into a liquid such as water, bubbles can be nucleated. These bubbles are created by forcing the dielectric breakdown of the fluid into plasma. The bubbles behaved like cavitation bubbles – they grew and then collapsed generating a shock wave. Sonoluminescence was also observed during the bubble collapse. These experiments studied the mechanism of creating these laser-induced bubbles and the shock waves generated but not their cavitation behavior or “lifecycle”. It was Werner Lauterborn, who in the early 1970’s, began his work studying cavitation phenomena at the University of Göttingen. Using high-speed photography cavity formation, growth, collapse, after bounces and non-linear behavior were studied. The advantage of using laser induced cavitation was that nucleation and nucleation position could be easily controlled and that the bubbles were mostly spherical. This allowed for the close study of the bubble dynamics. Results from the high-speed photography were compared to the Rayleigh empty-bubble model (spherical bubble model developed in 1917) with good agreement.

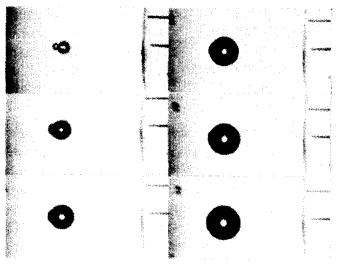

Figure: High-speed photography (547000 fps) of bubble formation in silicone oil leading to a spherical bubble; the time interval between successive frames is 1.83 microsecs

Today researchers still use the method of laser induced bubbles to study cavitation behaviour and sonoluminescence. Cavitation near a rigid surface is of high interest due to the need to clean components that are increasingly being manufactured on the micro or nano scale. Laser induced bubbles are a great way to study cleaning because of the high degree of control one has when creating these bubbles. However, it is not possible to create a large number of cavitation bubbles using a laser. That’s when ultrasound becomes a practical option; whether it’s for cleaning baths or micro-reactors where large populations of cavitation bubbles are needed. With that said, laser induced bubbles are from a pedagogical point of view one of the best ways to study the details of cavitation dynamics.

Dwayne Stephens, University of Göttingen

Sources:

W.Lauterborn: High-Speed Photography of Laser-Induced Breakdown in Liquids. Appl. Phys. Letters 21, 27-29 (1972)